Interview | Jocelyn Bell Burnell: “Yet another call on women”

11.5.2022

Since Jocelyn Bell Burnell started studying Physics in the University of Glasgow in 1961 she knew being a woman in science was not going to be easy. During a VISESS Big Picture Talk the astrophysicist and discoverer of pulsars, with her calm, but firm voice, took her listeners on a trip through a life of challenges, obstacles, but above all, love for science and determination to make it a better place for women and other minorities.

Jocelyn Bell Burnell, discoverer of pulsars, addressed the members of the Faculty of Earth Sciences, Geography and Astronomy on May 3 during a Big Picture event organized by the Vienna International School of Earth and Space Sciences (VISSES).

In a well-attended auditorium, she narrated the way that led to the discovery of these elusive astronomical objects. This discovery was so relevant, that it earned the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1974. Jocelyn, however, was not part of the recipients.

In a follow-up interview she shared a few more experiences on her fascinating life.

- We usually hear about great discoveries but are not aware of the long roads and pitfalls that lead to them. What would you tell young scientists in this respect?

It is true that there is a lot of hard work. It took two years to build the radio telescope. Two years working outdoors in all kinds of weather. Very healthy! But also, a lot of work. In Britain the PhD program is three years, so two thirds of my program were on building the equipment. We did not do the building full time. Typically, you would work in the mornings to build the equipment. In the afternoon there would be classes, or lectures, or discussions, or other work to do. It was quite a good mix. Healthy outdoor work in the morning and indoor intellectual work in the afternoon. For some people like me it was quite a lot of manual work. For other people it is perhaps more pencil and paperwork, or these days computer work. So, there is variety. Quite often when you are training as a researcher there is quite a lot of monotonous stuff.

- Which good memories do you have of your undergraduate time?

Some faculty members helped students understand things they were having trouble with. In my final year, the faculty member I and two of the men students met with was called Professor Drever, Ron Drever. Tiny little man, quite a round little man. A very good experimentalist with a very good understanding of modern physics.

We went to this tutorial. The three of us had agreed to see if he could help us with the solid physics course, because we were having trouble with that. We would go in and say, Professor Drever we don't understand solid state physics. Can you help us? He would say, no, I don’t understand it either. Let’s talk about the Hanbury Brown and Twiss interferometry or something like that. Really cutting-edge research, new results. Which is probably actually what undergraduates need, they need lifting beyond the course.

I made a mental note to watch any research field he worked in. He started working in gravitational radiation. I followed that field right from the beginning. And I knew there would be a discovery. I wasn't sure I would be around to see it. I was. We have it. It is great.

Jocelyn Bell analyzes what would become more than five kilometers of data from the radio telescope she helped build. Courtesy of Robin Scagell.

Jocelyn Bell Burnell working at the building site of the radiotelescope at the Mullard Radio Astronomy Observatory just outside Cambridge.

Foto: © Picture a Scientist

- "Picture a Scientist" - Online film screening and panel discussion on 24.05.2022 with Dean Petra Heinz, geophysicist Chi Zhang, Elisabeth Aufhauser (Geography) und Sylwia Bukowska (Head of division Gender equality and diversity at UNIVIE.

- Are there other not so nice memories?

It was quite tough because at that time it was tradition that when a woman entered the lecture halls all the men whistled, and stamped, and catcalled, banged the desks. These were wooden lecture theaters, so you could make quite a lot of noise quite easily. As the only female in the class I had to face that. I learned that you can control your blushing. I learned how to control my blushing. At least when faced with that I no longer blushed. I walked in still-faced and took my seat.

- Did that continue during the PhD?

No, partly because we had fewer classes. By then I had moved to Cambridge, and Cambridge was a very different kind of place. Full of young men from expensive schools who were absolutely convinced to their own brilliance. I, coming from Glasgow and from the north west of the country, didn't have that background. I found it quite daunting. That is when I started experiencing this impostor syndrome: they have made a mistake admitting me, I am not clever enough for this place. That led me to work very hard which in turn, I think, led to the discovery of pulsars.

- It seems that in Cambridge, apart from gender, other differences came into play.

Cultural background particularly. Scotland is very different from England. Particularly the south of England, which is where Cambridge is. In Cambridge it was much more polite, much more civilized. There weren’t the same issues there. There were issues that I felt an outsider. Up to then I had been up in the north west of the British Islands and this is the south east. It is affluent, it is flat, it is rich, it is cultured. And up north there, terrible primitive people. So, I was one of the terrible primitive people.

- Impostor syndrome is very common. However, it seems there is still very few information in universities to address this problem.

There is quite a lot of information in the web in general, you can find a lot on impostor syndrome. I think it is not recognized in universities. I guess it is only a minority of people that would experience it. If you are in a science that is majority male, some of the males may feel it, but most probably do not. Females in such an environment are more likely to address it. I think simply having information that there is such a thing would be useful.

I wasn’t able to name it for good many years. I could explain how I was feeling, but I did not know it had a name. I did not know others felt it. Actually, it was very common, especially in places like Cambridge and Oxford, but mainly mostly among undergraduates.

- What do you think could be done?

Impostor syndrome is now quite widely recognized. Certainly, in expensive top universities like Oxford and Cambridge we know to look out for impostor syndrome. Each autumn when there is a new batch of students some of whom are supremely confident, no issues, but others, more thoughtful ones, maybe get scared, maybe get impostor syndrome. We now know to look out for it and we know the name of it and we try and prevent students from rushing back home within the first week of being in Oxford or Cambridge. We are getting better all the time. We reassure those students: You had some very strict tests before you came here, you passed those tests. Many people did not, you passed those tests. That is why you are here. You are every bit as clever as everybody else here. No matter how they behave.

- You mentioned during your talk that feminism gains numbers as women get older. Why do you think this is the case?

I think as women become older, and hopefully a bit wiser, you see patterns repeating. You recognize repeating patterns and that helps. It does not always give you an answer but you say, oh, here we go again.

- As you advanced in your career, did you witness an attitude towards female students similar to what happened to you while studying in Glasgow?

Nothing like that. There are other more subtle issues. Like if you have a male and a female student doing a Physics experiment, what can happen is that the female takes the notes, she is the secretary, and the man does the experiment. Then you have to say, great, now, reverse roles. There are things like that to look for. That is not deliberate harassment. If you explain it to people, without blaming people, they understand, they can recognize it. If you blame people, the barriers go up.

- What would you say to young female scientists?

Science is a fantastic subject, lots of excitement, lots of interest. Go for it, get well dug in, enjoy it!

Discovery of pulsars

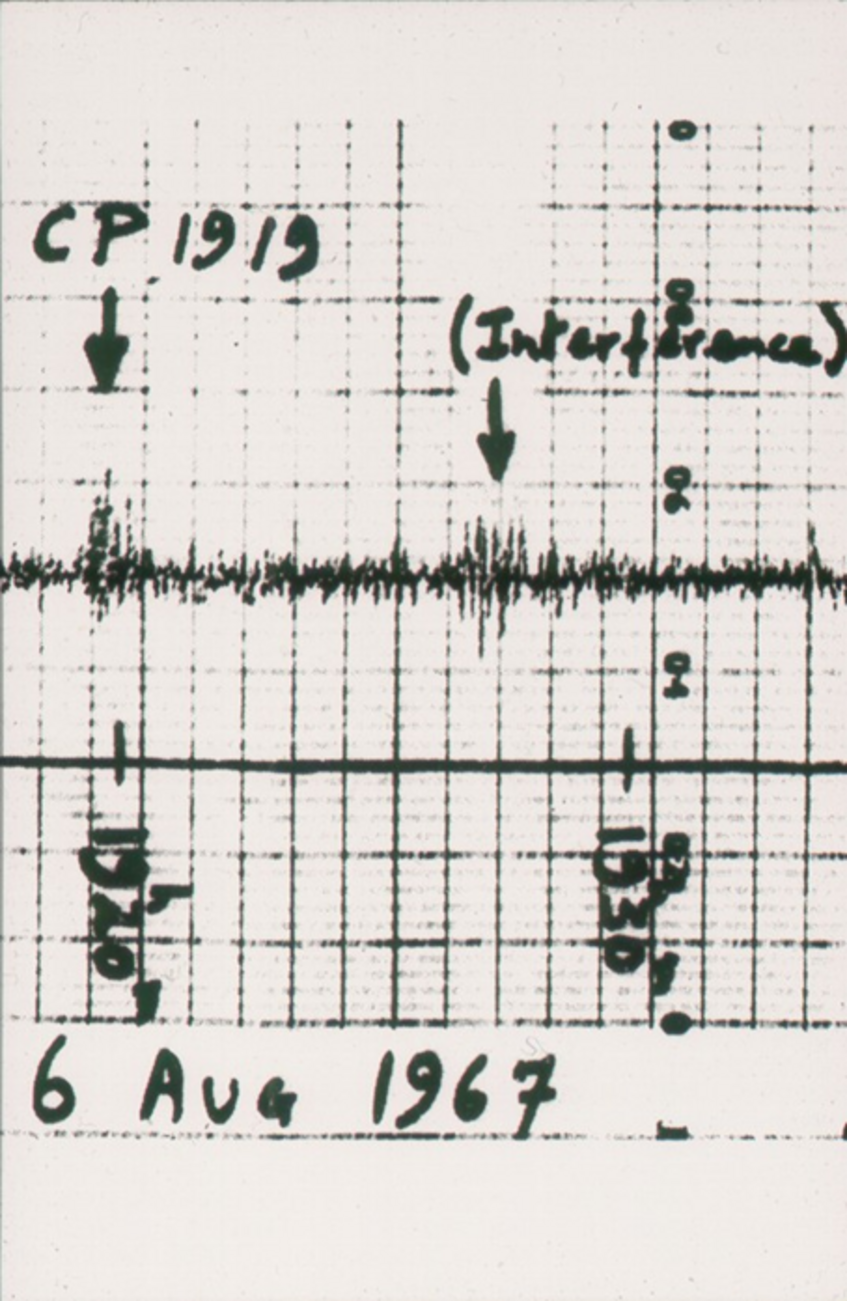

While doing her PhD on Radioastronomy at the University of Cambridge, Jocelyn Bell Burnell was analyzing more than five kilometers of data when she noticed a pattern that did not look like anything she knew before. This was something new! She had discovered pulsars. A pulsar is a collapsed core of a very massive star that is left after a supernova explosion. It is small and dense, and has very strong magnetic fields. Charged particles moving along its magnetic fields cause beams of radiation. Since the pulsar rotates very fast, these beams of radiation appear “to pulse”. These pulses are what Bell Burnell identified as a pattern in her data.

This discovery changed Astronomy and it earned the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1974. Bell Burnell was not part of the recipients.

Extract from the data analysed by Jocelyn Bell Burnell. On the right side a patch of interference is identified. On the left side is the signal of a pulsar.

Unconventional scientific career

Jocelyn Bell Burnell got married soon after the discovery of pulsars. Her academic life was influenced by this decision, as she had to constantly move places to follow her husband who was working for the government. On one hand this prevented her from building a traditional scientific career in which you follow up on your research interest for many years. On the other hand, mostly because of her strong character and decisiveness in not quitting science, she had the opportunity to work in different fields in Astronomy, from gamma rays to millimeter astronomy. In occasions her main responsibilities were not focused in research, but in lecturing at the Open University or managing projects at the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope in Hawaii, for example.

- You won the Breakthrough Prize for Fundamental Physics in 2018 and donated the 3-million-dollar award to create a program of scholarships for women and other minorities in science. This is not only a very generous deed, but a strong statement as well. Getting more women and minorities into science programs is the first step, but what should universities do to make the permanence more equitable?

I think it is worth making university academics aware that diversity is a strength. Some people don’t see any problem with the department being all white men. In fact, I think there is a problem, but they don’t see it.

Any organization is more robust, more intelligent, more successful, if it is diverse. Not just diverse in gender; diverse in race, diverse in as many dimensions as possible. I’ve been concerned that in Britain Physics is still very much white men. Undergraduate students are white men. I thought it would be good to use this money to increase diversity within Physics departments in Britain.

They appointed four students the first year, all young women, all young white women. They appointed eight new students in the second year, not all white, not all women. The process is still ongoing but they were hoping to appoint twelve students this year. It’s been building up quite fast, which is good. In terms of the overall numbers of research students it is still quite small. Departments welcome having another student funded and I hope it gives them some pause to think about why this is funded the way it is. I hope that the students who are funded actually do not have a difficult time because they are minorities.

- Finally, how have you found your visit to the Department of Astrophysics?

Huge fun. I have met so many interesting people and been given opportunities to meet so many people. Also, I’ve been taken fantastic care of. There are several young women who are really looking after me extremely well. Making sure I get meals, that I get to the right place at the right time. I fear I have taken up a lot of their time. Yet another call on the women in the department.

Jocelyn Bell Burnell with some of the organizers of the Big Picture Event. From left to right: Florian List, Josefa Großschedl, Jocelyn Bell Burnell, Christine Ackerl, Sudeshna Boro Saika, Anahí Caldú Primo, and Martina Egger.